Based on excerpts from notebooks I found while taking up the carpet in the attic in my Dad’s new house; some were heavily water-damaged, some I would not want to reproduce here.

Leveret Hackamore was born in King’s College Hospital, on August 19th, 1981. His given name, chosen by his mother, was not Leveret Hackamore, but that’s of little consequence, I think. Nearly two months premature, he spent his first weeks ensconced in an incubator, watched over in shifts by his mother, his father, and his aunts and uncles, of whom there were a considerable number.

The family knitted him minute garments; one-pieces, booties, a tiny woollen hat in cornflower blue. They ate fries from the hospital canteen in the soft light of the incubator, listened to the news on the handheld radio of one of the uncles. “Muammar Gaddafi today ordered the launch of two fighter jets to intercept American aircraft over the Gulf of Sidra,” it said. “Mark David Chapman has been sentenced to 20 years in prison for the murder of Beatle John Lennon.” Alvarez takes power in Uruguay.

Once they took him home from the hospital, Iris and James Hackamore (as we will call them) and their son lived in idyll for a number of years. With a booming economy and comfortable desk jobs on their side, the couple had bought a house in one of England’s soft southern counties, where Leveret grew up as a child should – loved, odd, and happy. From an early age, he would sit on the living room rug, and watch his parents’ records spin in their Sharp VZ-3500, mesmerised. His mother would choose Motown, Neil Young, and Paul Simon. His father, Springsteen. The Beatles. The Band. Iris, happening upon a sixteen-month Leveret banging on the rug with his fists and gurgling happily, called Jim in to see their son ‘talking to the song.’

Such was the boy’s fascination with music that he was encouraged by his parents to play various instruments – piano, violin, and eventually (when he talked them around to it) classical guitar. But, as it seems to have gone, nothing quite fit him right. His fingers would not fret, would mash the wrong keys in dissonant misbehaviour. Crotchets, minims and quavers swam before his eyes, melding to a dark and tarry mess. Impatient and frustrated with his inability to make a racket as magical as the records that he loved, Leveret would ditch each new instrument soon after starting.

It soon became clear that where he would or could not apply himself to learning music, Leveret did have a natural affinity for words. An early talker, he soon impressed English teachers with far-flung stories of unlikely heroes, their terrific surroundings rendered in improbable detail. His father, something of an outdoorsman, encouraged Leveret to ride his bike, play football, even fish (an unusual pastime for a child of his generation), but the boy showed little interest in these activities. Jim nursed a vague disappointment at his son’s lack of affinity with exercise, and sensing this, Leveret began to avoid Jim, instead trailing his mother as though linked by an invisible tether. Wherever she was, he was there also – at the sink, on the phone, knelt in soil in the garden, turning the earth with their hands.

When alone, though, Leveret was often to be found scribbling words and pictures in notebooks appropriated from his school’s store cupboards. The earliest of these that I could lay my hands on contains a story about a fresh-faced American guitar group called The Sparrowhawks (who ‘sounded like Tom Petty and The Band’), and their encounters with a gruff, childishly obscene punk rocker named Steven Weevil.

As Leveret grew up into a young man, his parents’ relationship would start to fall apart. After a succession of unlucky layoffs, Jim began to stay away from home at night, and the periods between his return grew longer and longer. Leveret would wake in the dark to the sounds he soon came to deal with by detachment; hushed anger, slammed doors, the clicking growl of an engine starting and fading into night. One bright summer day in Leveret’s tenth year, his parents took him to a public swimming pool, where they told him that his father would not be living with him any more.

This was also the year that Leveret first discovered Nirvana, whose Nevermind was released a little after his tenth birthday. Hearing Smells Like Teen Spirit on the radio, the young Leveret pleaded with his mother to buy him the single, which she did. The pair moved out of the house that Leveret had lived in since birth, and into an apartment, where they lived below a deaf lady named Margaret. She played the harmonium, an old Mason and Hamlin number which the pair listened to often through the ceiling, the songs punctuated by the short barks of her King Charles spaniel. From his voracious readings of interviews with his new favourite band, Leveret did his best to seek out the music of the names they mentioned – The Breeders, The Pixies, Sebadoh, Sonic Youth, Fugazi, and R.E.M. Encouraged by his mother to get a job, he rode his bike (a gift from the departing Jim) to an affluent neighbourhood on Sundays, where he would distribute handmade flyers with his home phone number, offering to mow lawns and wash cars. The proceeds from this kept him in singles, and copies of Melody Maker. Iris worked long hours to keep them both housed and fed, and Leveret was now left mostly to himself. After a time, he came to like things this way. He began to keep the house clean, and taught himself to cook from his paternal grandmother’s considerable collection of tattered and grease-stained recipe books, left uncollected by Jim.

Leveret’s nickname was given to him aged 15 by a schoolfriend named Tom, a boy with cerebral palsy and a 170 IQ. By the time they met, Tom had written librettos for two operas of his own devising. Both thought it a rite of passage to be given a nickname, and shortlisted theirs over tuna sandwiches in the school library one damp lunchtime. ‘Lev’ (as he was more often called) was Tom’s reference to his friend’s slight frame and twitchy demeanour. Lev called Tom ‘Butch’, in a clumsy, teenaged stab at irony. ‘Rabbit’ was not deemed interesting enough to denote the former; ditto ‘Mac’, the latter.

Butch, aside from sharing Lev’s ever-burgeoning love of books (which at this stage was preoccupied with George Orwell, John Steinbeck, Sylvia Plath and William Burroughs), introduced him to more music; they sat on Butch’s bedroom floor after school and listened to Subterranean Homesick Blues, The Lemonheads, PJ Harvey, Patti Smith, Sly and the Family Stone, De La Soul, Grant Lee Buffalo, Rage Against the Machine, Souls of Mischief, Idlewild, and Radiohead. The pair filmed an homage to Just on a Super 8 of Butch’s, a performance which would turn their cheeks red if they saw it now, and founded a school newspaper, in which they reviewed bands who would never play outside their parents’ garages and basements, bands with names like The Kites, Gasoline Picasso, and Curd.

As part of his physical therapy, Butch was encouraged to play the drums. Spurred on by his friend, Lev started to bring on his daily visits to Butch’s parents’ the unwieldy, nylon-stringed classical bought for him in his childhood. He endeavoured to learn three chords each day, which he took from a book called ‘Teach Yourself Guitar’, and the two would lash together rudimentary songs about books, boys, girls, food, school, their parents, and more. Lev began to bring the guitar to school, and lunchtimes were spent in the music department instead of the library. The pair would never play to anyone else, though, in this guise at least; at thirteen, Leveret’s guitar was taken and smashed by a group of boys from school, who held him down and sprayed him with deodorant, striking lighters to see if his clothes would catch. When this failed, they stuffed him in a wheelie bin. Appalled at what had happened to her son, and despite his protestations (and the mildness of his injuries – he came away with only a grazed back and a heavily-perfumed uniform), Iris made the decision to move again, it seems to the place my dad’s in now. Here, she tried through renewed attention to repair the weakened bonds that had once linked her and her son so strongly, bonds not frayed by malice or even lack of affection, but by Leveret’s conscious decision soon after the departure of his father; that if he were to live, he should never need the company of anyone but himself. But divested of Butch’s immediate proximity, he retreated to his room with Leonard Cohen, Eels, Elliott Smith, and would emerge only when required.

Lev and Butch wrote each other many letters and postcards, a useless but romantic affectation in the age of email. They fashioned zines by post, Dumbstruck, Chinaski’s Choice, and The APB.

“Distortion screams like arcwelders across my heart…”

“…awkward, whinging, nauseous guitar squall, terrifying blasts of weaponised fuzz-tone, the battle of super-ego, ego, and id.”

Her son’s withdrawal from warmth must have been difficult for Iris, but she rode out Leveret’s teenage years with unrelenting love and stoicism, and eventually, he began to appear about the house again, daily shedding self-involvement like dead skin.

Things tail off around here. Butch began to produce music on his computer, and would send the jungle-inflected results to Lev, who wrote about each new song as it came. Despite his friend’s entreaties, he never took up the guitar again. Judging from the most recent dates mentioned by Leveret, it looks like he and Butch made the move to the Internet sometime at the outset of 1998. Which leaves three things that I haven’t yet mentioned.

Leveret Hackamore’s favourite food is pasta – plain fusilli with cheese, how Iris made it for him as a child.

Leveret Hackamore’s adopted his ‘surname’ to round out a nom-de-plume; it was chosen in a dream, during a period spent reading only Cormac McCarthy novels.

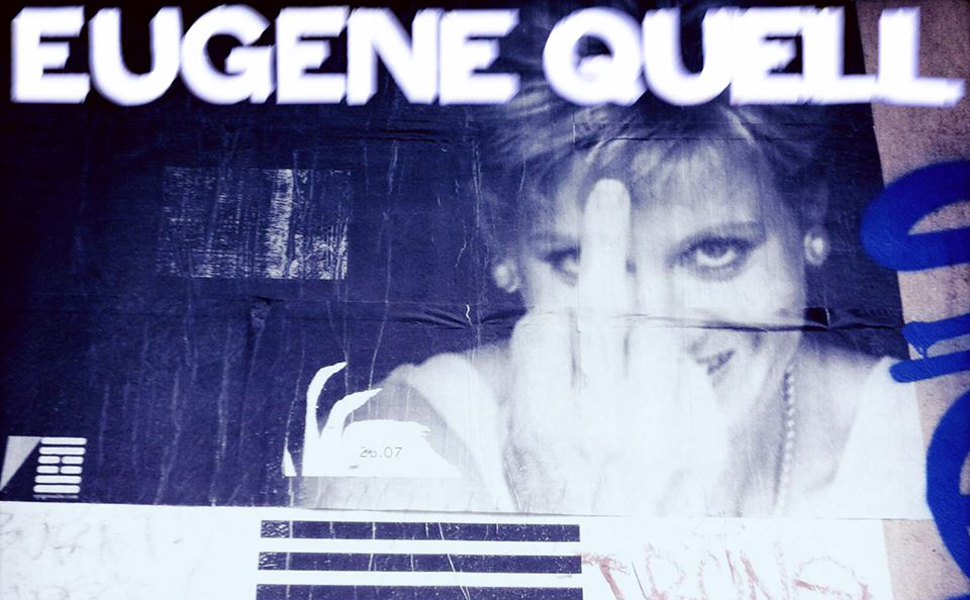

The last-mentioned musical artist in the notebooks of Leveret Hackamore is named Eugene Otto (‘Bud’) Quell.